The twenties were a time of stark contrasts in everything, including the successive presidential administrations, from the corrupt Warren Harding administration (1920-1923) to the asceticism of Calvin Coolidge (1923-1929), which served the purpose of creating a “businessman state. It was an era of materialism that triumphed in virtually every aspect of national life. Cinema, boxing, and baseball became big business and spawned their idols, such as Rudolfo Valentino and Greta Garbo, Jack Dempsey and Babe Ruth.

Almost as popular in 1920s America was the name of Sigmund Freud, the Austrian psychoanalyst of the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries who occupied the minds of European intellectuals. Freud explained to people that the true essence of personality lies in its subconscious sphere, which is based on three instincts: eros (instinct of life), tanatos (instinct of death) and libido (sexual instinct). He explained that a person’s childhood experiences are deposited in the subconscious in the form of “complexes” – the Oedipus complex (the son’s subconscious dislike for his father), the opposite “Electra complex,” and others – that the person can neither eliminate nor explain, and is therefore doomed to an agonizing struggle with himself.

In the twenties, Freud was on the lips of every educated American, even those who had never read his work. He was fashionable in Europe, and his theory effectively justified human drives. In the American materialist turn it produced skepticism, even cynicism.

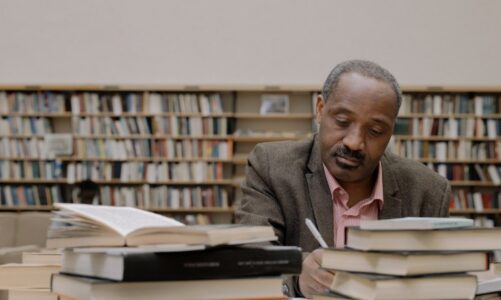

This time, which, with the light hand of F. Scott Fitzgerald, has been called the “jazz age,” was a time, not only of dismissive frivolity about life, but also a time when the arts flourished. Central and intriguing in its novelty, the cultural phenomenon of the 1920s was the so-called Harlem Renaissance, the sudden postwar flowering of “black” art in the United States, which, in fact, makes the decade the “century of jazz.

Beginning as a literary movement, the Harlem Renaissance involved the entire artistic bohemia of America’s black capital – artists, musicians, singers – and seemed to “open the borders” of the Negro ghetto. The new black art entered the life of the whole country; for a time Harlem became its intellectual and cultural center. The Harlem Renaissance was Duke Ellington, the first jazzman of the 1920s, the “black legend” of American jazz; it was professional tap singer Bill Robinson; it was singer Bessie Smith, the blues singer, the sweet chocolate dream of white boys who didn’t make it to the trenches and craved unusual sensations; it was the brilliant actress Ethel Waters and many others.

The new century has created powerful competitors to the book in the form of radio, movies, and big sports. At the same time, its technology, its expanding communications network, and its growing advertising industry fostered the creation of new magazines and new publishers. Publishers went after authors, magazines competed for the right to print their stories; writers began to earn more, and their audiences expanded considerably. With the advent of the sound film era in 1927, Hollywood began to attract many famous writers, such as Fitzgerald, Faulkner, Dashiell Hammett, Nathaniel West, with unheard ofly generous contracts. Most writers, however, felt rather discouraged at the sight of the nation’s shameless pursuit of money.

If in the twenties the ruler of thoughts was Z. Freud with his concept of personality, now it was Karl Marx with his critique of capitalism. Marx’s ideas in the popular interpretation of domestic “Marxists” (Joseph Freeman, Michael Gold, etc.) were very widespread and sympathetic in America. “The Red Decade,” “the angry decade,” was how the 1930s were defined in American culture.

Hitler’s rise to power in Germany (1933), the threat of a new war that shadowed all of Europe, the brutal persecution of Jews by the Nazis – all these interrelated events forced hundreds of writers, artists, musicians, scientists and philosophers (both Jewish and non-Jewish) to seek refuge in the United States. Thomas Mann, Vladimir Nabokov, Isaac Bashevis Singer, Albert Einstein, and others are the immigrants of this wave.

However, despite the complicated situation in the world, America remained too preoccupied with its domestic problems to give up its policy of neutrality. “America First,” the name of an isolationist organization, was the slogan of many Americans. Subsequently, however, it became clear that full economic recovery could only come about after America joined the World War II countries, an action that accelerated its rise as a world power and radically changed again the life of the nation, its culture and literature.

Until the middle of the twentieth century, New England literature was considered “American,” Midwestern, Southern, and Western literature was considered “regional,” and the work of Jewish and African American writers was considered “minority” literature.