A favorite parable of the creative youth of the twenties was the story of how a 36-year-old gentleman, owner of a thriving paint factory in Illyria, Ohio, suddenly left his business (and also his family) and went to Chicago to find meaning in art. The gentleman’s name was Sherwood Anderson (1876-1941), and he became one of the pioneers of modernism in the United States and the founder of a new type of American novel.

Anderson’s biography before this radical turn was typical of the “average American” who made his way in the world by his work. Raised in a large family of Southerners who moved to the Midwest in search of work, he volunteered to fight in the Spanish-American War, then served as an advertising agent in Chicago, briefly attended college in Springfield, opened a paint company in 1906, only to abandon it six years later and start life anew.

In fact, the turning point in his fortunes that occurred in 1912 was the result of a nervous breakdown rather than a conscious “conversion” to art. The results were nonetheless striking, though more enriching to American literature than Anderson’s. One of the “gurus” and patrons of young American novelists remarked that “the only thing he can teach is anti-success.” Anderson’s writing biography is indicative of the fate of the American literary man of the 1920s and 1930s.

He was published in Chicago magazines, and when he had no money, he made extra money writing advertisements, was friends with the poets of the “Chicago Renaissance” of the 1910s (Carl Sandberg and others), in 1921 he lived in France, where he became friends with the talented writer-expatriate and a great original, Gertrude Stein (1874-1946). This lady declared earnestly: “The Jewish nation has produced only three original geniuses – Christ, Spinoza and me. She was also a thoughtful mentor to the young American talent of the twenties (Paris was their Mecca at the time), particularly E. Hemingway.

Sherwood Anderson became the literary “godfather” of William Faulkner: while living in New Orleans (1922-1923), he met the aspiring novelist and later helped him with the publication of his first novel. Anderson’s own novels – The Marching Men (1917), The White Poor Man (1920), Across the Desire (1923) and others – as well as his journalism (America in Confusion, 1935) are interesting and characteristic phenomena of American literature of that period. But Anderson’s true discoveries and his enormous role in the development of American literature are connected with the short story genre.

The short story, as we remember, occupies a special place in the literary history of the United States. With the publication of Irving’s Rip Van Winkle, a distinctive national literature began. The novellas of Irving, Hawthorne, and Poe, along with the novels of Cooper and Melville, propelled it into the forefront of the world. At the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, however, there was a crisis of the genre. The traditional short story with its dashingly twisted action and indispensable happy ending, established with the works of J. London, Bret Harte and O. Henry, had practically exhausted its possibilities. Most importantly, it ceased to correspond to the spirit of the times, the postwar revaluation of old values and the rejection of optimistic illusions.

The twenties saw a radical change in the American novel, which reflected the shifts in social attitudes of the time and at the same time defined the development of the genre in the United States for decades to come. This turning point is associated, above all, with the name of S. Anderson. In 1919 he published a book of short stories “Winesburg, Ohio,” then “The Triumph of the Egg” (1921), “Horses and Men” (1923), “Death in the Woods” (1935).

The short stories in Anderson’s books were unlike anything that had appeared in American literature before. Nothing happened in them, they lacked a plot in the proper sense of the word. All the events and facts were hidden in the subtext. The center of gravity here was shifted from intrigue to revealing the psychology of the hero, a detailed study of his emotions. Each of the short stories described a small, unremarkable piece of reality, in which, as in a compressed spring, the fates of people, their joy and their pain were contained. The reader, to the extent of his or her reading and human experience, was free to unwind this “spring. The main “element” of such short stories was a tremendous emotional tension, also hidden in the subtext.

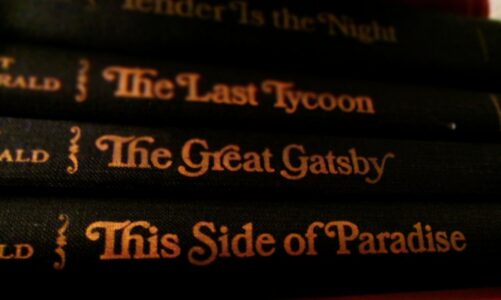

Anderson’s innovation in the field of the short story genre had a huge impact on all contemporary writers in the United States. He became the father of the American novel of the twentieth century. Hemingway, Faulkner, Fitzgerald, then Steinbeck, Caldwell, Updike, Saroyan, Salinger and many others followed. The tradition of the “hero-grotesque” was developed independently in national literature.