The most noticeable since the American Renaissance of the 1850s qualitative change in U.S. literature, the “second flowering”, as critics have designated it, occurred in the postwar 1920s. World War I traumatized the national consciousness and shook the traditional American optimism considerably, but at the same time it also pushed the boundaries of the United States, previously closed to most Americans. In addition to the fact that many American writers (or would-be writers) had fought in Europe and served in foreign armies (their European experience was often limited to trenches and hospitals), the country as a whole joined the fate of Europe, sharing it as it were.

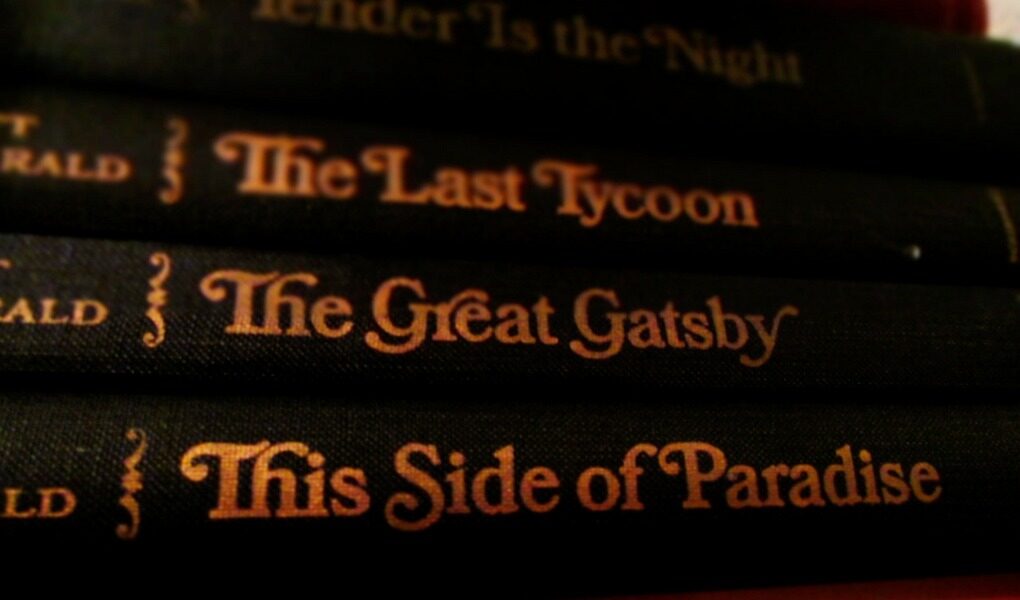

The main aesthetic event of the European literature of the twenties was modernism with its characteristic perception of life as chaos and widespread moods of melancholy and hopelessness, fueled also by the memory of the decadence of the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, by the ideas of O. Spengler. Spengler’s ideas of the “twilight of the gods” and the “sunset of Europe. The atmosphere of postwar America, which had lost many of its illusions, was quite consistent with these ideas. Emory Blaine, the hero of Scott Fitzgerald’s 1920 novel This Side of Heaven, did not go to war, but “grew up only to discover that all gods were dead, all wars had died, all faith undermined. America did not survive the turn of the century in the European manner, but displaced it in time and combined it with the aesthetic upheaval of modernism, which reflected the inner world of man after World War I extremely vividly and impressively.

Modernist art was not a means of influencing the world morally, but a way of creating an alternative world – the world of the artwork, the precision and accuracy of which formed a kind of counterbalance to the chaotic and monstrous absurdity of life around. In contrast to the reality absolutely beyond human control, senseless and hostile to him, the proportionality of the proportions of this world was entirely determined by the skill of the artist, had an independent aesthetic sense.

In addition, the modernist approach to art allowed unrestricted freedom of creativity and artistic experimentation. For American writers, it allowed them to overcome both the “puritan limitations” of national culture and the “pervasive commercial spirit” of the economic boom, which were equally destructive for the creative personality. The modernist approach to art and to life: daring experiments in narrative technique, bohemianism, expatriation – was the way out for American writers, especially for the younger generation, from the newly provincial framework of the national literature. “Something subtle and elusive has permeated America,” wrote F. Scott Fitzgerald, “a way of life.