Of course, not only the work of R. Wright and not even only African-American poetry and prose – the literature of the United States “red decade” as a whole was as sharply different from the postwar, as the America of the 1930s, the period of the Great Depression, the America of the “jazz age”. Artistic prose and journalism, experiencing an unprecedented flowering during these years (T. Dreiser’s Tragic America. Dreiser, Anderson’s America in Confusion, Fitzgerald’s Collapse, Hemingway’s abundant “Spanish” publicism, etc.) is a literature of great social content and the strongest political potential. American writers retained the creative impulse of the previous decade, but channeled it in a new direction.

The general reorientation of fiction was reflected in the treatment of authors to a new range of problems, the main of which were, first, the labor movement (strikes, strikes) and the lives of ordinary people and, secondly, the fight against fascism (especially the war in Spain). Thus, S. Anderson portrayed the textile workers’ strike in North Carolina (“Across the Desire,” 1932), J. Steinbeck in a new way, with greater social certainty, approached his favorite theme – the plight of American farmers (“The battle with the outcome of doubtful”, 1936; “Grapes of Wrath”, 1939).

E. Hemingway, one of the brightest representatives of the “lost generation,” also turned to socially significant problems in these years. The topic of the labor and farm movement was never organic to him (in his novel To Have and Have Not, he ironically depicted the literary man Richard Gordon, who was “writing his fourth novel about strikes”). Hemingway turns to what he himself experienced and felt – the anti-fascist struggle in Spain, to which the novel For Whom the Bell Tolls.

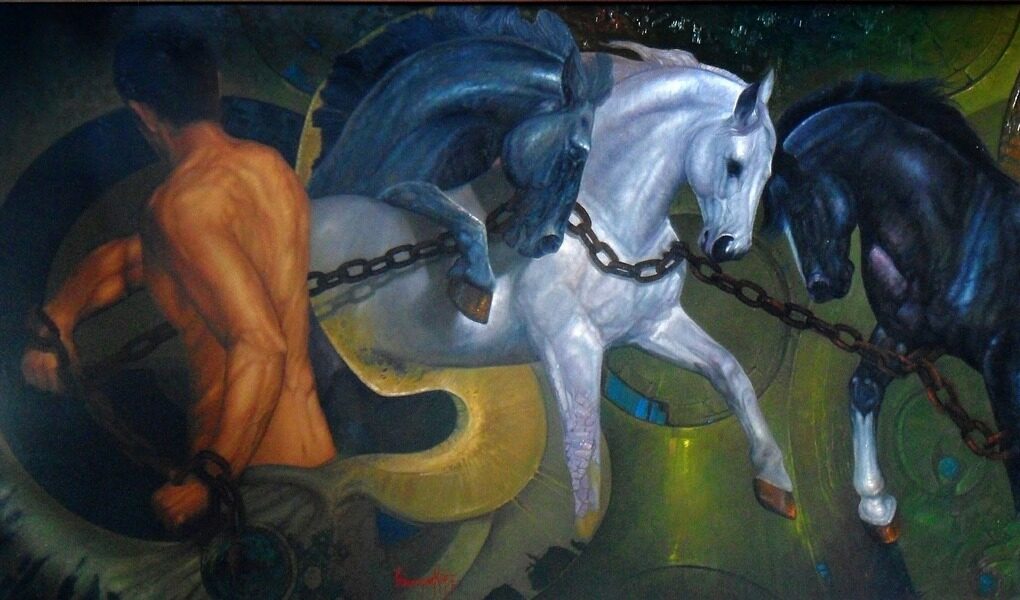

Changed issues required and other than before the principles of implementation. For works written in the 20 th years, was characterized by lyrical reticence, depth in the inner world of man. They mediated the entrance of the outer world. The thirties saw a broadening of the range; social reality directly invaded the books of American authors, who found a gravitation towards the universal coverage of events and, consequently, to the epic principles of representation. The prose of the thirties was predominantly epic.

Thus, John Dos Passos attempted to create an “American epic” – the trilogy “USA”. It included the novels “The 42nd Parallel”, “1919” and “The Big Money”. Variants of the modern epic also appear much smaller novels “Grapes of Wrath” (1939) Steinbeck and Hemingway’s “For Whom the Bell Tolls”. Both were written at the end of the 30’s and soaked up the atmosphere of the “angry decade.

The novel “For Whom the Bell Tolls” (1940) reveals a clear continuity with the works of Hemingway 20s. Events are passed through the perception of the confused hero, who is shown at a crisis point in his biography. The composition is based on the principle of “compressed time”. The action of the novel covers only three days. Robert Jordan, an American volunteer, is on a mission. He has to blow up a bridge in the rear of the Frankists. During these three days, Jordan manages to live, in fact, a whole life, to feel the whole gamut of human feelings: the happiness of love, the joy of solidarity, the pain for his comrades, whom he is forced to risk.

An extreme manifestation of the reorientation of U.S. fiction in the 1930s was the emergence of openly propagandistic social protest novels as a mass phenomenon: critics have counted more than 70 works of this genre, released in the country for one decade. The creators of these novels were mostly proletarian authors; many of them first turned to literature at the call of class consciousness.

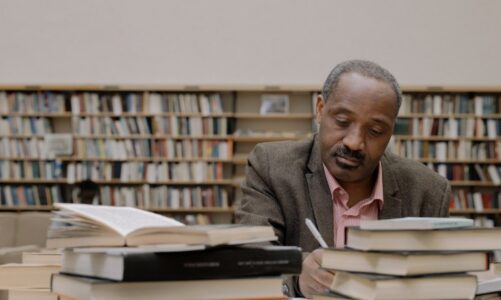

Significantly, the second generation of Jewish-American writers (first-generation Americans), born before World War I and who spent their childhood in Jewish ghettos, contributed greatly to the social novel of protest: Michael Gold, Edward Dahlberg, Alva Bassey, Albert Maltz, Howard Fast, Tilly Olsen, and many others. They entered literature in the “red thirties,” which determined the general thrust of their work. More precisely, in many respects it was they, fascinated by the ideas of Karl Marx, the Russian proletarian revolution, and the proletcult, who defined the “red” character of the “angry decade” in U.S. literature.